Norton Health Law, PC is pleased to announce that Vincent W. P. Prior, Esq. has…

I Almost Got Fired for Answering This Question

The question I probably get asked more than any other is, “How did you go from being a nurse to being a lawyer?”

Originally, I wasn’t even sure I wanted to be a nurse when I started nursing school. My mom had wanted me to be a nurse and I liked the idea of helping people, but it wasn’t exactly a career I was passionately pursuing. I had been pre-med before I dropped out of college, and since I was a single mom and felt medical school was out of the question for me, nursing seemed like the next best thing. Besides that, there was a nursing shortage, so job security wouldn’t be an issue and I thought a nursing career might provide a decent life for me and my girls. Not a super inspiring story by any means.

On my first night of nursing school, we had to go around the large lecture hall, introduce ourselves and tell everyone why we wanted to become a nurse. Pretty much every other person before me said they had wanted to be a nurse since they were a little girl (there was only one guy in the class), so when it was my turn, I wasn’t sure what I was going to say. I mean, when I was a little girl, I wanted to be Madonna so I couldn’t say that, and I certainly didn’t want to admit that I was not looking forward to changing strangers’ bedpans or diapers, which is pretty much what I thought nursing was when I was a kid.

Of course, by then I knew nursing was an incredibly challenging and complicated profession that requires not only a strong stomach and an understanding of the human body, but also advanced critical thinking and communication skills. And it didn’t take me much longer to learn that as soon as a person became my patient, they weren’t a stranger anymore and I would do anything to make them better or more comfortable, including changing their bedpan or even holding their hand when they die.

One day while I was still in nursing school, I went to the doctor with an intense pain in my abdomen. I was told I would need a $3,000 procedure to find out exactly what was going on. The doctor was worried that I might have a serious, if not fatal, condition, but there was just no way I could come up with that much money. I was already working full time during the day and going to school at night, and just barely keeping a roof over our heads and food in our mouths.

I was terrified and angry because it seemed so unfair to me that I could die for no other reason but that I was poor. It made me feel worthless.

By the grace of God, my doctor felt compassion for me and agreed to perform the procedure for free if I agreed to explain the procedure to my nursing classmates, and I did. Overwhelmed with gratitude, I bawled my eyes out right there on the exam table.

But not everyone experiences that kind of grace.

A few years later, I was working in the Emergency Department overflow unit at Virginia Beach General Hospital and was taking care of two patients I’ll never forget. They were in exam rooms directly across from each other. In one room was a man in his late 60’s who had Medicare and a private healthcare insurance plan, and in the other room was a 36-year-old woman and mother of three small children who had no insurance. She and her husband had lost their health insurance when the Ford plant where they had worked for 15 years closed.

She had severe asthma and came to the emergency department several times a month to get nebulizer treatments whenever she suffered an acute attack. Her asthma had been well controlled when she had insurance and could afford to buy the inhaler that controlled it. Without insurance, though, that drug cost several hundred dollars, which of course, the family couldn’t afford.

The emergency treatment she received at the hospital was far more expensive, of course, but the law required the hospital to provide stabilizing treatment for her regardless of her inability to pay, so there she went. Often. She was a “frequent flyer,” which is what the ED staff affectionately called people in her situation. We would feed and entertain her three kids for hours while she sat in the bed wearing the misty mask over her face.

It made absolutely no sense to me. The hospital and/or the state were going to end up paying for this treatment that cost many, many times the cost of that already expensive name brand medication, so why wouldn’t the state just buy it for her? Wouldn’t that be a win-win for everybody???

Then there was the man across the hall. He had COPD and also relied on that very same expensive name brand medication, but he didn’t even have to think about how much it cost or ever know how many times it kept him out of the ED. In fact, one evening, he left the inhaler on his dinner tray and didn’t realize it until someone from dietary had already picked up the tray. I called the dietary department to see if they could find it, but it had apparently already been dumped in the trash.

No worries for him, though. I was able to go into the Pyxis machine and get him another one at no cost. As I was walking to his room with it, I glanced over at the woman and thought, this is so stupid and unfair. It made absolutely no sense to me that it should be so easy for one person to receive a medication and so impossible for another to receive the same one. That was the first time I remember thinking, “somebody needs to do something about this.”

After many, many other such moments, I decided I didn’t want to wait for somebody else “to do something” about the problems I encountered in the healthcare system – I wanted to do something. I had absolutely no idea how I would do that or what the answers would be, but somehow I determined the best way to figure it out would be to go to law school and pursue a career in healthcare policy and patient advocacy.

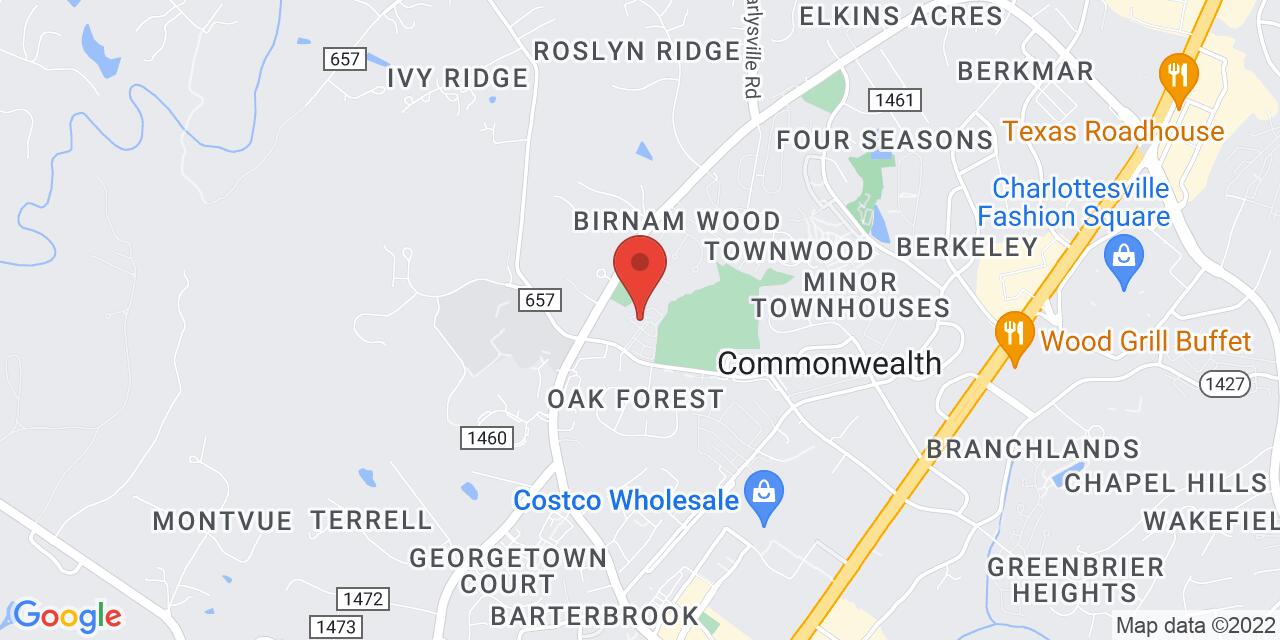

While I was in law school, I was told many times I would have to work at a law firm for at least five years before I could forge my own path because I had to learn how to practice law. More specifically, I had to learn how to practice healthcare law. I was lucky enough to get a job with the law firm in my hometown with the best health law reputation, first as a summer associate in law school, and then as a full-time associate.

About a month after I started at that firm, I was approached by a reporter at the Virginian Pilot who had seen the announcement the firm had taken out in the paper about me as their new lawyer. She thought my nurse-turned-lawyer story would make an interesting article in her “day in the life” column.

Of course, one of the first things she asked me in our interview was why I decided to leave nursing to pursue a career in law. I recounted some of my frustrations over the state of the healthcare system and my concerns about patient safety in one particular hospital, although I didn’t specify which one.

The day the story was published, many of my colleagues came by my office to congratulate me on the “great article,” although I have to admit I was just mortified by how tired I looked in the photo they used. I was also a little embarrassed that some of the things I was quoted as saying were a little off.

And then my boss called me into his office. He told me that the CEO of one of the hospitals I was quoted as having worked for, also one of the firm’s biggest clients, called him and basically said, “WTF? How could you let your associate trash us in the paper like this?” I was absolutely horrified and I was sure I was about to be fired. The sad thing was, his hospital wasn’t even the one I was talking about when I described the conditions as “dangerous.”

Thankfully, my boss defended me and told the CEO the reporter had misquoted me and taken the things I said out of context. And even more thankfully, I wasn’t fired. But that interview was the last time I would talk openly about the dangerous conditions I had witnessed as a nurse. From that point forward, when people would ask me about the transition from nursing to law, I would just talk generally about the state of the healthcare system and wanting to make a difference.

Until now.

I’m extremely grateful for the knowledge and experience I gained from my years in the corporate health law world, and especially for the relationships that resulted from my time with them. But I’m also grateful that I’m no longer tasked with protecting healthcare corporations and that I can finally speak openly about my experiences working within them. I feel extremely blessed that I’ve reached the point in my career that I can finally speak out about the realities and injustices of our healthcare system and that I get to spend the rest of my life advocating for real people as they fight the uphill battle of getting the care they need and deserve.